Washington, D.C.

14 MINUTE READ

Student Achievement Highlights

- In 2019, D.C. was one of only two jurisdictions in the country to improve on three out of four National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exams, and has made more total progress than any state in the years this version of the test has been administered.

- From 2007 to 2017, improvement in fourth-grade reading and fourth- and eighth-grade math among D.C. students outpaced 26 other large urban districts by at least double. Student achievement has improved in both charter and district schools.

- From 2007 to 2014, the percentage of students achieving proficiency on state tests increased by 14 percentage points in reading and 24 percentage points in math. Scores improved over this time period in both charter and traditional schools. After the switch to new, more rigorous tests in 2014, upward progress on proficiency over time has continued.

Summary (2007-present):

- Long-serving and best-in-class charter authorizer focuses on school quality

- Local leaders and community members open innovative school models

- Distinct sectors and agencies collaborate and support coordinated enrollment

- Evolving accountability framework offers consistent measurement

- School supply remains ongoing challenge

- 2020 Washington, D.C. Update

Washington, D.C. is a city of paradoxes: It is the capital of a nation that champions democracy, but its own citizens long lacked a democratic vote in their governance. As the seat of power of one of the world’s richest nations, D.C. sees nearly 17 percent of its residents living in poverty, much higher than the 12.3 percent national average.

These paradoxes and inequities have also been reflected in the District’s public education system; for decades, D.C.’s schools ranked among the lowest-performing jurisdictions in the country. But in the last decade, D.C.’s schools have improved more rapidly than just about anywhere else. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test, a biennial exam given to students across the country, measures math and reading progress in 4th- and 8th-grade students. D.C. is one of its “happiest stories.” D.C. gained the most ground of any jurisdiction in 4th-grade reading and 4th- and 8th-grade math, with point gains at least double that of any other jurisdiction since 2007.

The same paradoxes that once placed D.C. among the nation’s lowest-performing school systems have also shaped its educational resurgence. The district’s progress has been fueled by a high-performing charter school sector, with results that have outpaced traditional schools, making it central to D.C.’s story. Federal legislation established the charter school option, but local educators and leaders led the growth of these schools. D.C.’s strong, independent authorizer has overseen quality by putting in place systems and mechanisms that protect charter autonomy while also holding schools accountable for results, and works with partners in the city to support school choice. And as the charter sector has increased choice for families, it has also created political will that enabled the traditional school district to undertake bold reforms and improve its own results.

Far from the corridors of federal politics, local D.C. leaders are building a system of quality schools — and accountability and choice mechanisms to support them. Other cities can learn from D.C.’s strong central authorizer, coordinated opening of new schools combined with the closing of low performers, a performance framework, and a district-wide universal enrollment system. Yet while D.C.’s progress has been groundbreaking, these innovations have not solved the ongoing need for more high-quality schools. Achieving a true system of choice requires more high-quality open seats, either near the students’ neighborhoods or with good transportation options.

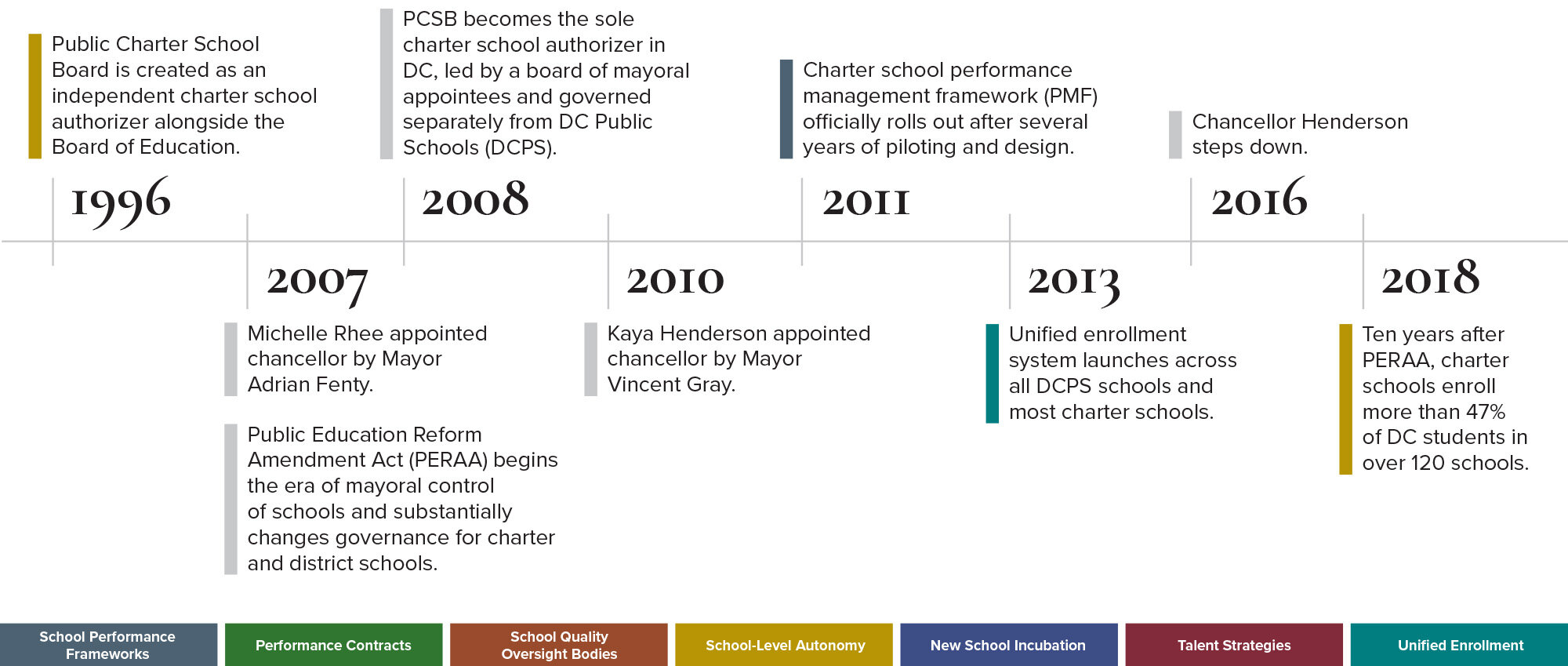

The rapid improvements that drew national attention began in 2007, but the story of the District of Columbia’s educational progress began more than a decade earlier. The District of Columbia School Reform Act of 1995 allowed public charter schools, a relatively unknown type of school operator, in the District of Columbia and gave authority to grant charters to the Board of Education (BOE) and a newly created entity, the D.C. Public Charter School Board (PCSB).

This was still early in the national charter movement, so PCSB leaders needed to figure out how to implement the new law. Josephine Baker, a longtime district resident, teacher, and associate professor of education, became a founding member of the PCSB and would serve as its executive director from 2002 to 2011. “We had to build this from zero with a committed board whose goal was to serve children,” Baker says. This meant that PCSB and charter schools in the district often had to do things few authorizers or operators had done before, including balancing individual school autonomy with the board’s authority to close low-performing schools.

Unlike cities where the charter sector grew with an influx of large national charter management organizations, D.C. built from within. New schools were largely founded by local parents, educators, and community leaders, building a school culture where parents felt connected and, in turn, supported school leaders. Former PCSB Deputy Director Naomi Rubin DeVeaux notes this reflects a culture where “relationships are everything — we are a small town.”

School operators from the local community proved an early asset to meeting student needs. In 1998, Linda Moore founded Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School, named after her mother, with a vision of a culturally diverse student body learning in two languages — English plus Spanish or French. Moore is just one of dozens of D.C. education leaders and school founders who PCSB Executive Director Scott Pearson describes as a “diverse group of extraordinary entrepreneurs” who thrived in this new, more autonomous sector. Other founders named their new schools after such icons as Cesar Chavez, Mary McLeod Bethune, Euphemia Lofton Haynes, Maya Angelou, and Thurgood Marshall. Some charter school operators offered specialties such as arts, technology, dual language, or Montessori. This approach has resulted in a diverse portfolio of charter schools. As Moore reflects, school systems need to have “as many educational options and school models as the students need. ‘One size fits all’ does not work.”

“ ‘One size fits all’ does not work.”

Not all charter schools thrived: From 1996 to 2007, 15 schools would close. But Stokes and other effective schools quickly attracted community interest, building long waiting lists of students seeking a high-quality choice. As parents voted with their feet, moving their students from district schools to charter schools, the sector grew. By 2007, the charter sector enrolled 21,948 of the 71,071 total students in the district, or 30.9 percent.

Skip McKoy

For D.C. Public Schools (DCPS), the loss in enrollment exacerbated an already difficult situation. The district had endured both a union and BOE financial scandal and decades of fiscal and administrative mismanagement. Perhaps most discouragingly, DCPS students had the worst NAEP reading scores among 11 big cities, in an urban district with already high per-student expenditures. Faced with this reality, Mayor Adrian Fenty and the D.C. Council enacted the District of Columbia Public Education Reform Amendment Act (PERAA) in 2007. This legislation transferred control of DCPS from an elected school board to the mayor, created a chancellor role to oversee DCPS, and paved the way for bold improvements.

This legislation and Fenty’s subsequent appointment of Michelle Rhee to the chancellor role drew national attention. But the legislation also made several other less-noted but equally significant changes that shaped the evolution of education in D.C. over the next decade.

PERAA unified all charter school authorizing under the PCSB to streamline oversight and created two new coordinating offices: the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) and the Deputy Mayor of Education (DME), which support coordination and oversight across both the district and charter sectors.

PERAA spurred improvement in both DCPS and the charter sector. As the new sole authorizer in D.C., PCSB absorbed 18 BOE-authorized schools, many of which were struggling. This challenge would push PCSB, which was already regarded as a national model authorizer, to develop practices and systems to improve the charter schools they oversaw and raise the bar for charter school quality overall. In many areas, PCSB evolved over time, bettering its approach to challenges with a learning mindset shaped by what worked and what didn’t. This relentless self-assessment with responsive improvements is instructive.

One concrete example of an innovation resulting from this pressure is the Performance Management Framework (PMF), which established a comprehensive and more equitable system of measuring charter school performance. With a growing number of schools pursuing unique educational missions and focuses, there was also variation in quality. PCSB needed to create a clear, common standard for the outcomes all schools must prioritize and a simple way to communicate those outcomes to leaders and families. The PMF places schools in tiers based on their score — Tier 1 for high-performing schools, Tier 2 for mid-performing schools, and Tier 3 for low-performing schools — using an index that incorporates multiple indicators of school performance. Former PCSB board member and Chair Skip McKoy says the PMF became a “leveler” by applying the same standard to all schools.

In designing the PMF, PCSB sought to hold schools accountable for a more comprehensive definition of school quality than test scores alone while also maintaining a clear focus on schools’ academic performance. Today’s PMF focuses on five areas, including student growth, student achievement, readiness for college and career, enrollment and attendance factors, and a school’s mission alignment. At its core, DeVeaux emphasizes that the PMF asks schools to teach students to “read, write, and do math.” This approach enables the PMF to accommodate a variety of different school models and teaching styles while holding all schools to a common, high standard. Daniela Anello, head of school at DC Bilingual Public Charter School, appreciates this framework and says, “[The PMF] is a pretty good tool to be held accountable to, and we like how it is consistent year after year.” Pearson emphasizes the PMF’s importance in creating a “consistent and predictable accountability environment” and in informing decisions about both school growth and closure.

The PMF’s ability to provide a fact-base that informs school closures is an important lesson for systems considering such a tool. Clear expectations from the outset have made it possible for the PCSB to close low-performing schools in a more fair and transparent process. During charter application processes, for example, the PCSB staff use the PMF to communicate expectations to prospective applicants. DeVeaux is clear with charter school applicants: “I point out if you become low performing, you will be closed.” Moore believes the authority of PCSB to close schools made her school better: “The fear of being closed has made us pay close attention to the measures used to determine whether we are an effective school.”

Since 2007, PCSB has closed 35 charter schools or programs, and Pearson notes that “a lot of our energy is spent on ensuring that any fair-minded person who looked at the process would say that this was even-handed.” Pearson explains that schools get “lots of notice” if they are in danger of closing, often two to three years before their five-year charter review. McKoy says that the board always asks, “Have we given the school enough time?” PCSB invites the low-performing school’s board in for direct conversations to analyze school-level data, target areas of improvement, and work toward a solution.

Scott Pearson

One of the barriers to closure is a lack of adequate seats in other high-performing schools, an issue that PCSB has sought to address through expansion or replication. Since 2006-2007, 38 campuses or programs have opened. These new schools have included campuses operated by high-performing operators from other jurisdictions, but the results of such expansions have been mixed; some outside operators struggled due to lack of community connections or an understanding of D.C.’s culture. Successful locally operated and effective single-site schools are also encouraged to open additional campuses. After launching in a Northeast D.C. church basement in 1998, Moore’s Stokes School opened a second campus in fall 2018. The Stokes East End campus provides 140 new pre-kindergarten and kindergarten seats, crucial in D.C.’s chronically underserved Wards 7 and 8, which are located east of the Anacostia River and have the city’s highest concentration of children in poverty. The school will gradually expand to serve 400 pre-K through 5th-grade students. If successful, this may be the harbinger of other high-quality expansions.

The combination of common performance measures and expectations, closure of low-performing schools, and growth of high-performing operators has improved achievement for D.C.’s charter students. From 2006 to 2014, the percentage of PCSB students who demonstrated proficiency on the D.C. Comprehensive Assessment System (CAS) tests — the primary assessment used at the time — rose from 36 percent to 57 percent. Even with the adoption of more rigorous tests designed by the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) in 2015, scores have continued to increase in math and English for both 4th- and 8th-grade students.

The number of students in high-performing charter schools has grown by 12,000 since 2011, and the number of students in the lowest-performing PCSB schools has been cut by more than half, from 3,900 to 1,685 students. More students are moving to the schools and school models that best serve their needs — and that offer a quality education and other features families seek.

As PCSB increased high-quality options for D.C. students, DCPS experienced the competitive push of district alternatives. To achieve gains of its own, DCPS has used a more centralized approach. Rhee’s three-and-a-half-year tenure resulted in rapid and often discordant changes to DCPS, including a system-wide teacher evaluation and pay-for-performance strategy known as IMPACT. Her successor, Kaya Henderson, continued Rhee’s reform agenda during her subsequent six years as chancellor. During their administrations, some 43 schools closed, driven primarily by financial, demographic, and facility considerations — not school performance.

In a city where students are almost evenly split between the charter and traditional sectors, system-wide coordination is advantageous wherever possible. So, despite their differing strategies, DCPS and PCSB have built cross-sector systems to foster equity and support parents in making school choices. District-level coordinating agencies OSSE and DME also play a crucial role in these efforts.

One way the agencies have joined forces is to build a much-needed universal enrollment system. DME led this effort and needed the full cooperation of DCPS and PCSB to create and oversee a complex system. Enrollment for virtually all open seats in both sectors, except adult education, is managed through My School DC, an online platform where families can apply to up to 12 schools and rank their choices. My School DC helps level the playing field for parents and families, using an enrollment algorithm to place students based on their choices. Before the system existed, parents had to apply individually for each school they were interested in, go through multiple lotteries, and keep track of many different school-specific deadlines and requirements. This exacerbated inequities for low-income families due to the time and effort required.

While still imperfect, universal enrollment has benefits not just for families but also for schools. Before the universal system, school-based enrollment directors had to deal with parents forgetting to notify schools if they didn’t intend to enroll their student, leading to a “September shuffle.” Maura Marino, CEO of Education Forward DC, recalls how disruptive this was: Schools faced “rosters which were just changing constantly” in the first month of the school year, a problem that has been somewhat mitigated by universal enrollment. Despite promises of a smoother process, many charter operators initially hesitated to relinquish the autonomy to run their own enrollment. But Moore says Stokes’ staff members actually find the new system “much easier.” This ease of use has meant some initially skeptical charter schools now participate in the system, even though participation is voluntary.

Maura Marino

Anello vividly remembers the world before universal enrollment. Even as head of school, she received no preference when it came to enrolling her son at DC Bilingual. She recalls attending the enrollment lottery event, where she sat on the edge of her seat, wondering if his number would be drawn. The principal was almost through pulling numbers for a mere 19 open slots when her son’s number was picked. Anello burst into tears of joy.

As a parent and school leader, Anello knows firsthand that the demand for quality schools has not subsided. This past year, nearly 2,000 students applied for a handful of open slots at her Spanish/English dual immersion school. Though no one is pulling numbers from a hat any longer, the lack of enough high-quality options creates a de facto roll of the dice for parents.

Despite the current universal enrollment lottery, clear data on school quality, and myriad choices in both district and charter schools, many families still don’t have confidence that their child will be educated in a high-performing school. In 2018, 64 percent of students overall got a My School DC match, meaning they were offered a spot in one of the schools they chose. One-third of students are not being matched to any of their ranked options, demonstrating an ongoing lack of adequate seats. The lesson is clear: While universal enrollment is better than the previous inequitable and often confusing system, even the best tools will feel inadequate if your system does not have high-quality seats available for all students.

D.C. has made progress in student achievement, but the system as a whole still faces significant challenges requiring continued cross-sector collaboration. Decisions made by and for both sectors will shape the future of D.C. schools. Whether they continue working together to increase quality seats in a system with equitable, true choice will determine if the next era will be one of progress or one of decline.

March 2020 Update

The past few years in Washington, D.C. schools have been marked by big leadership transitions within the charter sector and DC Public Schools (DCPS), but these leadership changes have not resulted in significant strategy or policy changes in the city’s schools.

In early 2018, DCPS Chancellor Antwan Wilson and Deputy Mayor for Education Jennie Niles both resigned because the chancellor’s daughter had been allowed to bypass unified enrollment systems and waitlists to enroll in a highly sought-after school. This scandal came shortly after the revelation that one in three students in 2017 received their diplomas in violation of attendance and credit rules that could have disqualified them.

Lewis Ferebee was confirmed as DCPS chancellor early in 2019. Ferebee was formerly superintendent in Indianapolis, whose similarities with D.C. include a unified enrollment system, school performance framework, and school-level autonomy. And in November 2019, Public Charter School Board executive director Scott Pearson announced he was stepping down after eight years of charter authorizer leadership.

Enrollment in both charter and traditional schools increased modestly in 2018-19, but initial enrollment numbers for 2019-20 revealed the first enrollment decreases for charter schools since 1996. This came about as more families opt in to their neighborhood schools, and the Public Charter School Board closed several charter school campuses according to their performance contracts, which the mayor and charter school leaders framed as an expected part of D.C.’s charter school model.

2019 results on the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP) showed good news for both DCPS and the city’s public schools as a whole: D.C. is one of the only jurisdictions in the country making continuous improvements in NAEP performance, and continues to grow quickly relative to other urban school districts.

The following organizations are or were clients or funders of Bellwether: D.C. Public Charter School Board, Elsie Whitlow Stokes Community Freedom Public Charter School, D.C. Public Schools, Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, DC Bilingual Public Charter School, and Education Forward DC. Bellwether authors maintained editorial control of these stories.